Published January, 2015 by Sam Gregory in Video for Change

Do We Need a Dedicated Repository for Human Rights Media?

I’ve been discussing frequently with my WITNESS colleagues the question of whether the human rights community would benefit from a shared database (public or private) or online video-sharing site that would show the breadth and scale of human rights violations worldwide, and enable coordinated action. Jokingly, I refer to it as the “one ring to rule them all” phenomenon, referring to the inscription on the controlling magical ring in Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

Here are some of our thoughts and experiences of the value of these options.

Lessons Learned from The Hub: A public online destination for human rights footage

From 2007 to 2010 WITNESS ran the first dedicated online sharing space for human rights video – the Hub. It was focused on human rights content, contextualized and linked to action, and called attention to security issues. It was consciously a non-corporate site, built with open-source software, and aimed at the emerging community of NGOs and citizens sharing human rights footage online. Yet, after three years of operating it, in 2010 we archived the existing content on the site, and stopped accepting new content. What did we learn from the experience?

The challenges of promotion: How do you get people to the platform? How do you make sure uploaders know it exists? Even though we had a large network of human rights organizations that we had trained and engaged with worldwide, more often that not they were already using mainstream platforms that were gaining prominence, like YouTube.

This promotion challenge becomes even more pronounced when we consider that the target audience was not only professional human rights activists and NGOs but also the citizen witnesses, journalists, and activist media collectives who often document in situations of crisis. Those individuals were (and are) accustomed to sharing their footage on YouTube, Facebook and other locally-specific platforms. So even as we talked (half-jokingly) about our “YouTube for human rights,” YouTube was indeed already, in its less visible depths and breadths, a YouTube for human rights.

![By avebae (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://blog.witness.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Cute_Cat_2.jpg)

By avebae (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Additionally, it’s less likely that the broad public will care that your human rights site goes down. At the time of the Hub, Ethan Zuckerman wrote thoughtfully about the risks specialist social justice sites face in his ‘cute cat’ theory of the Internet – i.e. that it’s much harder for governments to block the sites that the average citizen finds his or her daily fix of cute cats on, than it is to block the specialist site that he doesn’t usually turn to. There is no broad public outcry over that. The cute cats, in effect, help protect serious human rights content.

The Tech Arms Race

There was also a very pragmatic reason why WITNESS, as a medium-sized human rights NGO, stepped away from running a public video-sharing and social media platform. We realized that we were in a ‘technology arms race’ with exactly those platforms that our primary users were already turning to. Rapid advancement in technology means that platforms must be able to adapt quickly and add the features that users expect or run the risk of becoming obsolete.

A screen capture of the face blurring mobile app ObscuraCam, from the Guardian Project and WITNESS

After the Hub, WITNESS has taken two distinct approaches to this technology arms race. On the one hand, we partner with the ‘best-in-class’ open-source activist technology developers to support the creation and implementation of tools that address key human rights needs.

For example, we partnered with the Guardian Project to develop ObscuraCam and InformaCam, and to promote them both within the activist community but also as reference designs to the broader mainstream for ideas like a widespread ‘proof’ mode.

And on the other, we partner with existing platforms to find ways to enhance the accessibility, safety and presentation of human rights content within the commercial mainstream. We worked with YouTube to launch the Human Rights Channel, a Channel on YouTube in partnership with Storyful, that verifies, contextualizes and curates key human rights content and to introduce a blurring functionality and a way to provide guidance to human rights users within the platform.

An ‘evidence locker’ for critical footage?

One idea that we do think has traction is a reflection of the dangers of relying on commercial sites like YouTube to be a public repository for critical human rights footage. As a recent survey of the content shared on the Human Rights Channel found, at least 5% of the 6,000 videos shared in the past two and a half years have since been deleted, removed or made private. And the decisions of YouTube around what footage is permissible on the platform, although they allow for the public interest value of otherwise unpleasant and graphic footage that would be removed, do sometimes result in the removal of exactly the type of footage that is needed for human rights evidentiary and investigatory purposes.

We’ve been exploring a number of alternatives to protect this content for human rights purposes. Could YouTube itself retain copies of otherwise-“unlisted” content for designated human rights purposes? Or could groups like Storyful or autonomous institutions like the Internet Archive collaborate with human rights organizations like WITNESS to more effectively scrape and store videos which may have potential investigatory, public interest or evidentiary value? And could they collectively preserve them with as much metadata and clear evidence of chain of transmission?

A whistle-blowing destination for human rights content?

Another area that we’ve considered – especially in the light of our work on InformaCam with the Guardian Project, is the role of a general human rights whistle-blowing site to which people can securely send images and video (InformaCam is a tool to allow the secure transmission of verified, metadata-enriched video to someone you trust.) Is there a space for one (perhaps much like the original vision of WikiLeaks)?

WITNESS itself made a decision not to offer itself as a destination for any human rights footage that any user might shoot with InformaCam – how would we know how to route it, and to make sure the expectations of action that every submission carries with it, are fulfilled? Better it seems to support a range of sites specific to different contexts that are built on an infrastructure of interlocking, inter-operable open-source tools. That’s why InformaCam relies on another open-source technology, Globaleaks, for secure transmission.

A shared database of human rights footage?

Another iteration of the global destination considers whether a shared archive or database of human rights information (including videos) is possible between a range of human rights organizations at a local, regional and global level. Here information could be shared within the human rights community but kept confidential or private for a general public. Perhaps this is to much to hope for, given the trust that would need to exist between all these actors. However, the potential for a different vision of this shared archive exists already. There are models within the library world – including the LOCKSS project (“Lots of Copies Keeps Stuff Safe”), an open-source system with hardware that libraries can use to collaborate and to store each others’ “stuff” ( in this case, journals).

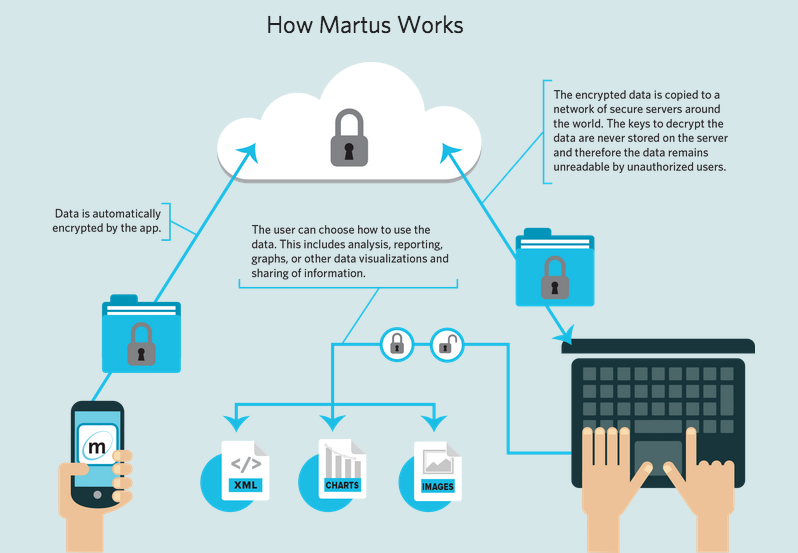

This vision of a shared archive also exists in the form of interoperable standards for description and exchange and in the thesauri used in the documentation of events, and in tools like Martus that enable secure documentation to the cloud. This seems a more plausible direction to enhance and explore – and we’ve been focused on that, by trying to increase understanding of how to archive and manage video with our Activists’ Guide To Archiving Video.

Conclusion

All of these questions remain very live ones for us here at WITNESS as we try and enhance the capacity of a growing and diversifying human rights movement to use video – and we’re open to learning more about how any of these approaches could be done better. Please comment or tweet us.

Featured image by DRs Kulturarvsprojekt via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]

Sam Gregory is the Program Director at WITNESS. Sam also leads on the Technology Advocacy program and the Mobil-Eyes Us initiative. You can follow him on Twitter @SamGregory.