Published August, 2016 by Sam Gregory in In the News, Mobile Phone Video, Video for Change

Immersive Witnessing: From Empathy and Outrage to Action

We are in the moment of an explosion of opportunity and hype around the possibilities of the ‘wildfire’ of immersive media – the ‘empathy machines’ of virtual reality and the breathless urgency of personal live-streaming video via Facebook and Periscope.

There has been a wave of recent virtual reality experiences that take human rights issues and immerse audiences in experiences of being there. These include projects like Clouds over Sidra and other UN-affiliated media on human rights and humanitarian crises, as well as mainstream human rights journalism like the New York Times’ The Displaced and advocacy journalism like the Guardian’s exploration of solitary confinement in the 6×9 project. They also include immersive animation capturing refugee journeys like We Wait from BBC and Aardman Animations and Nonny De La Pena’s work with computer graphic generated simulations based on real footage and audio that includes Project Syria and a range of other topics.

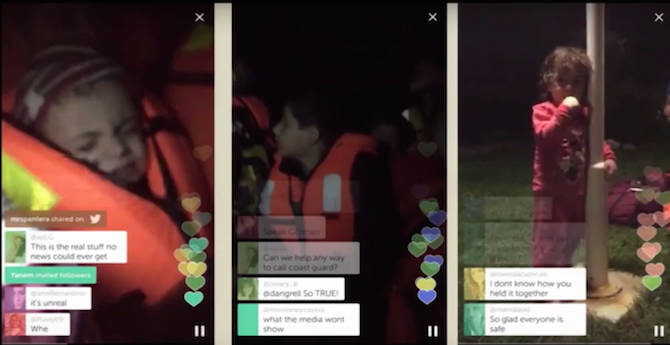

Until recently less discussed – perhaps because of their ephemeral, more marginalized and more unpolished nature – is a growing wave of live media-making that places us with protagonists at the heart of crisis, from the #NoBillNoBreak broadcasting of US Congressional Representatives, to eyewitnesses to an attempted coup in Turkey, to Paul Ronzheimer’s broadcasts of refugees traveling to Europe to, of course, Diamond Reynolds’ heartbreaking live documentation of the aftermath of the shooting of her boyfriend, Philando Castile. It’s innovation sparked by the growth and availability of Facebook Live, Periscope and other platforms and feeding into contemporary social justice struggles at an individual or group level.

Recently I have spoken about the opportunities and challenges for social change efforts, including human rights journalism, advocacy and activism facilitated by a range of media approaches and technologies that share a set of technological and experiential characteristics. These immersive media experiences (borrowing from a definition of virtual reality from the Tow Center for Digital Journalism report) that i) immerse us in an real or imagined environment, ii) allow the audience to interact with it and iii) to feel as if they were there: i.e. they contain three critical elements of immersion, presence and agency or interaction.

To me, this spectrum of technologies and media that enable immersive advocacy, activism and witnessing includes not only computer-generated virtual reality, but also immersive 360-degree video, as well as live and increasingly immersive (360-degree) live video.

For more, here’s a video of a recent talk (or alternatively, see main points below).

TL:DW/ TL:DR Version

There are challenges and opportunities in virtual reality, live and immersive media for social good.

- 1) Attention and denial in the face of tough stories and information overload. Attention deficit and the implicit and explicit denial of bystanders are primary challenges in human rights. Immersive media experiences can help through their capacity for embodiment, place illusion and interactivity but we need to avoid complacency.

- 2) Spectatorship or witnessing?: These tools can reinforce trends towards self-expressive spectatorship rather than genuine witnessing. We need to be very aware of this, as well as the possibility we reinforce an emphasis on dramatic moments not structural causes.

- 3) Empathy or something else? Yes, these tools can contribute to empathy. But is empathy what we privilege over understanding, compassion, solidarity, or action?

- 4) We need to think about going from presence in other peoples’ lives to co-presence: from ‘being there’ to ‘being there together’ and what this can mean in terms of action with impact. Here immersive live media could play a pivotal role and we’re exploring it with our Mobil-Eyes Us initiative.

The challenge of denial and how virtual reality and immersive media’s capacity for embodiment, place illusion and interactivity can help.

Let’s face it…People are mostly not interested, willing or available to engage with the narratives and experiences we share or tell about human suffering and resilience in the face of crisis. Simply and more bluntly, the poet Philip Larkin noted in a letter to a friend bemoaning some domestic situation the bland, underlying reality of communicating other people’s realities and understanding them in relation to our own crises.

“Yours is the harder course, I can see. On the other hand, mine is happening to me.”

The core question for any visual media confronting human rights atrocity is how does it confront the denial of audiences that don’t want to see it, hear it, listen to it, experience it or react to it.

Stanley Cohen, who wrote extensively on how people deny human rights suffering notes this can take the form of literal denial: “There was no massacre.” “There is no homelessness in my town.” It can also be interpretative denial: “It was population exchange, not ethnic cleansing.” “Those are people who made a purposeful choice to come to this city without housing.” And it can also be implicatory denial: “It’s got nothing to do with me.”

These denial responses can be in terms of cognition (not acknowledging the facts); emotion (not feeling, not being disturbed); morality (not recognizing wrongness or responsibility) as well as action (not taking active steps in response to knowledge).

How we confront this question of denial is particularly important when we compete in a marketplace of billions of images in which Aylan Kurdi’s body on the beach may have broken through into people’s consciousness but it is the rare exception (how many pictures of refugee corpses on beaches did we not see before and have not seen since?) and even as a mainstream image it’s competing in an image marketplace with the images that “break the internet” like Kim Kardashian.

In these situations, bystanders’ acknowledgement and intervention is less likely when:

- Responsibility is diffused

- People are unable to identify with victim

- People cannot conceive effective intervention

- Distant bystanders lack texture of rich, personal experience and direct risk

There are real opportunities here in terms of immersive media and virtual reality’s affordances.

Virtual reality and immersive live video has a capacity for embodiment: either literally feeling like you are someone else, or that you are ‘walking in someone’s shoes’, both in point-of-view 360 video as well as volumetric (computer-generated) virtual reality.

Virtual reality has a capacity for place illusion – the sense that we’re in a real place – even in less than fully-rendered environments (see for example this research). In volumetric, computer-generated virtual reality there is the possibility of a sense of interactive agency with the environment. In immersive 360 and immersive live we can experience a rich sense of co-presence (the feeling that “we’re in this together”) and in immersive live video we can experience the possibilities of real-time interaction and action.

Are we engaged in self-expressive spectating or active witnessing?

The second challenge is how we distinguish self-expressive spectating from witnessing in solidarity. Witnessing is a concept key to both activism and journalism – the role of being there, of purposefully and intentionally sharing what you see, and of acting.

A classic definition of witnessing emphasizes elements that include:

- The direct act of seeing and then purposeful sharing on with intentionality

- The correlation of witnessing to embodied presence at the time and place of the violation (in journalism, this is the foreign correspondent doing his stand-up in the site of crisis)

- The possibility of risk and trauma to the witness.

Immersive media reality potentially enables witnessing because of its capacity to give us a sense of embodied presence in the context of a violation, crisis or human rights context.

However, we have to be careful of the relationship of this immersive experience to problems of poverty tourism, i.e. experiences that brings us close to someone else’s suffering but allow us to retreat when we are discomfited.

Beyond that we need to ask if the immersive and interactive nature of these experiences induce a sense of agency to explore narcissistically? Or do they generate an alternative form of agency – to experience, understand and to feel compelled to act in the interests of the people who are affected by the social injustice?

Our immersive media advocacy risks perpetuating a trends in activism and engagement towards a self-expressive activism that the academic Lilie Chouliaraki describes as taking ‘the emotionality of the donor, rather than the vulnerability of the distant other, as a key motivation for solidarity’. Under these circumstances our engagement with activism takes the form of a ‘theatrum mundi – a theatre whose moralizing force lies in the fact that we do not only passively watch distant others but we can also enter their own reality as actors.’ In this theatrum mundi, ‘narcissistic indulgence in the authenticity of the self’ is privileged over the genuine solidarity centered on the needs or underlying concerns of the distant other.

Because of the limitations of the form, to-date, many contemporary virtual reality experiences are largely sold on its ability to place us next to the action for 5 minutes, and then retrieve us. And some approaches to live immersion posit the same. They drop us into an intense experience but don’t ask us to do much more than gasp. We have to be careful of that “OH GOSH, I CRIED” reaction and focus on the vulnerability and needs of the frontline activist as a motivation for solidarity and action. This is not a puppet theatre.

Is empathy enough? Choosing compassion and solidarity over empathy.

Empathy and understanding won’t just happen because an experience is immersive or has an individual has a sense of presence. Research and experimentation suggests embodiment can contribute to a stronger understanding of another person’s experience (and conversely that empathy avoidance can also take place if we’re exposed to traumatic experiences which implicate us in ways we are unwilling to take on), but virtual reality, despite assertions to the contrary, is not an automatic ‘empathy machine’.

However, more important to me is whether empathy is enough or even what we want. Should we not instead be pursuing understanding, compassion, solidarity and action? Empathy is an overrated emotion in activism, while the role of compassion and solidarity are often under-valued. Compassion is the capacity to see, observe, feel and then step back and take reasoned action in the interests of another. Solidarity is the ability to walk alongside someone else, to act with them, and yet recognize your ability to both know and not know their struggle.

Here in the context of virtual reality, to engage compassion and solidarity is a storytelling challenge. There are opportunities in multi-perspectival and kaleidoscopic virtual reality storytelling that allows for multiple viewpoints or multiple paths to be explored as a tool for enhancing compassion. Examples of this to-date include Rose Troche’s Perspective series that places us inside multiple perspectives on sexual violence and police conduct or The Enemy‘s attempt to bring us face-to-face with combatants on different sides of critical global conflicts. There are also possibilities of live media and co-presence (‘being together with’) that I discuss below.

Can we communicate structural violence and beyond the graphic or dominant media moment?

A similar opportunity exists in using story worlds and use arcs of storytelling that might also move us over time through understanding, empathy to compassion, solidarity and action. This is most critical when it comes to communicating structural violence. As it stands, the emotional intensity of virtual reality and immersive experience may inadvertently contribute to the ongoing challenge in human rights of communicating structural violence, hidden violence and underlying causation, by giving a false understanding of historicity and causation based on narrow bursts of emotionally intense experience. Communicating structural violence is often the biggest problem human rights advocates face. As the founder of Partners in Health, Paul Farmer, writes about in relation to Haiti,

“Structural violence all too often defeats those who would describe it … To explain suffering, one must embed individual biography in the larger matrix of culture, history, and political economy.”

Or to take a reference closer to the world of images, James Agee in ‘Let Us Now Praise Famous Men’ famously describes a cotton-field worker he met :

“How is it possible to be made clear enough… the many processes of wearying effort which make the shape of each one of her living days; how it is to be calculated, the number of times she has done these things, the number of times she is still to do them; how conceivably in words is it to be given as it is in actuality, the accumulated weight of these actions upon her; and what this cumulation has made of her body; and what it has made of her mind and of her heart and of her being.”

How do we communicate those ‘wearying’ hours in virtual reality and immersive media? Or one of the worst things about refugee camps – the ongoing existential limbo? My suspicion is that this will take the form of thinking what the Instagram or Snapchat of virtual reality feel like, the ephemeral or episodic conversation that brings us close on an ongoing basis, that makes us feel close to our friends even though we’re far.

What are other ethical questions of immersive experience, including the risk of vicarious trauma?

There are a range of other ethical questions that we can raise about immersive and embodied experience of other’s trauma. One particular concern from a human rights perspective is related to questions of denial and to the issue of empathy avoidance from experiencing a sense of guilt at being confronted with another’s suffering, and that is the issue of vicarious trauma induced by images and experiences. A correlated experience relates to how we understand our own ethical duty to watch or not watch death on camera, particularly in circumstances where we are acting purely voyeuristically; this is intertwined of course with debates about the role of technology companies in moderating, taking down or deleting live-streams on their platforms (and issue we’ve grappled with here)

For a greater range of potential ethics questions, and an initial approach to a broader ethical code, I recommend the paper from one of my co-panelists at a recent talk at MIT, Michael Madary.

From presence to co-presence

A potential counterpoint to some of the challenges and opportunities above helped inspire a project we’ve been working on at WITNESS.

In this video excerpted below a policeman approaches a media activist in a protest in Brazil. He is about to conduct what may be an illegal search. The policeman says “Watch the search” and the activist who has been livestreaming says: “I will watch. There are 5 thousand people watching it. “

Here, the tables are turned. The watching audience matters. Rather than being passive spectators, or self-involved spectators they have become witnesses acting on behalf and with the media creator and frontline witness.

One initiative we’ve been incubating at WITNESS – Mobil-Eyes Us – takes this possibility of us as distant witnesses watching livestreams of human rights and social justice situations to propose a model for moving from passive viewing. We aim to use the power of live video (and the ability to bring the right stream to the right person) to connect people who are not physically present in situations of crisis to particular powerful experience of issues they care about, and to particular meaningful actions that draw on what you do best.

If a frontline activist or media-maker or even an ordinary citizen confronted by injustice could ‘summon’ a crowd of 100 observers and virtual participants or even just one with the right skills, what could they achieve? If we could stand alongside them, what could we achieve? Our excitement here is around live, immersive experience and the opportunities it provides for viewers to be embodied with and as, and for the opportunities for the possibilities of co-presence (‘being together with others’). We move from watching others and experiencing their realities to co-existing immersively in a space together with others across geographical distance but in the same moment in time.

And like many other areas, this approach to VR exists at the intersection of growing investments of the tech industry (see of course Mark Zuckerberg’s comments on the future of Facebook) in immersive live video, virtual reality, and to a lesser extent, haptic technologies.

We’ve been exploring how to create an arc of immersive live co-present moments that engage people in meaningful solidarity and action with others from bringing people into the iconic spaces and intimate meetings of organizing to ‘witnessing with us’ and leverage options that make the presence of multitudes of distant viewers more visible in the site of activism or behind the closed doors of power. We’ve been exploring how to create rapid reactions around live, immersive events and how to amplify critical moments. We’re also particularly interested in the role of sharing moments of joy in order to motivate and engage participation and ongoing action. As activists like Saul Alinsky reminds us, struggle is also about the moments of hope. Joy and solidarity after even small victories are what keep us going. Immersive joy media matters too.

Looking ahead, so-called haptic tools (that transmit physical sensation to engage our sense of touch and feeling) like hug jackets and pulsing bracelets can make the feelings of distant others visceral and tangible via touch and sensation – so that someday soon someone in crisis can feel the warm glow or uplifting energy of solidarity around them. For it’s that experience I care about more – not that we can feel what it is like to be the frontline activist (and to experience a self-fulfilling rush), but that the frontline activist can feel and know that we have their back.

As we move ahead as a field of human rights and social justice practitioners using immersive virtual reality forms, I think these are critical questions to ask. What would you add?

- How do we effectively turn empathetic experience into action? Is empathy what matters for understanding or action?

- When it comes to telling challenging, trauma-laden stories – how do we make sure our audiences come back (in the face of trauma, denial, image overload) after the initial novelty wears off?

- What is meaningful (co-present) interaction that levels the playing field between participants with headsets, and watching on their mobile devices, and participants in the real world of live and recorded immersive experience? (aka viewers and subjects)

Shortly we’ll share more on this from upcoming pilots and tests including some work around the social justice impacts and the alternative side of the Rio Summer Olympics. If you are interested in collaborating on this work, do contact us.