Published February, 2016 by Sam Gregory in Legal/Ethical, Safety & Security, Technology / Equipment, Uncategorized, Video for Change

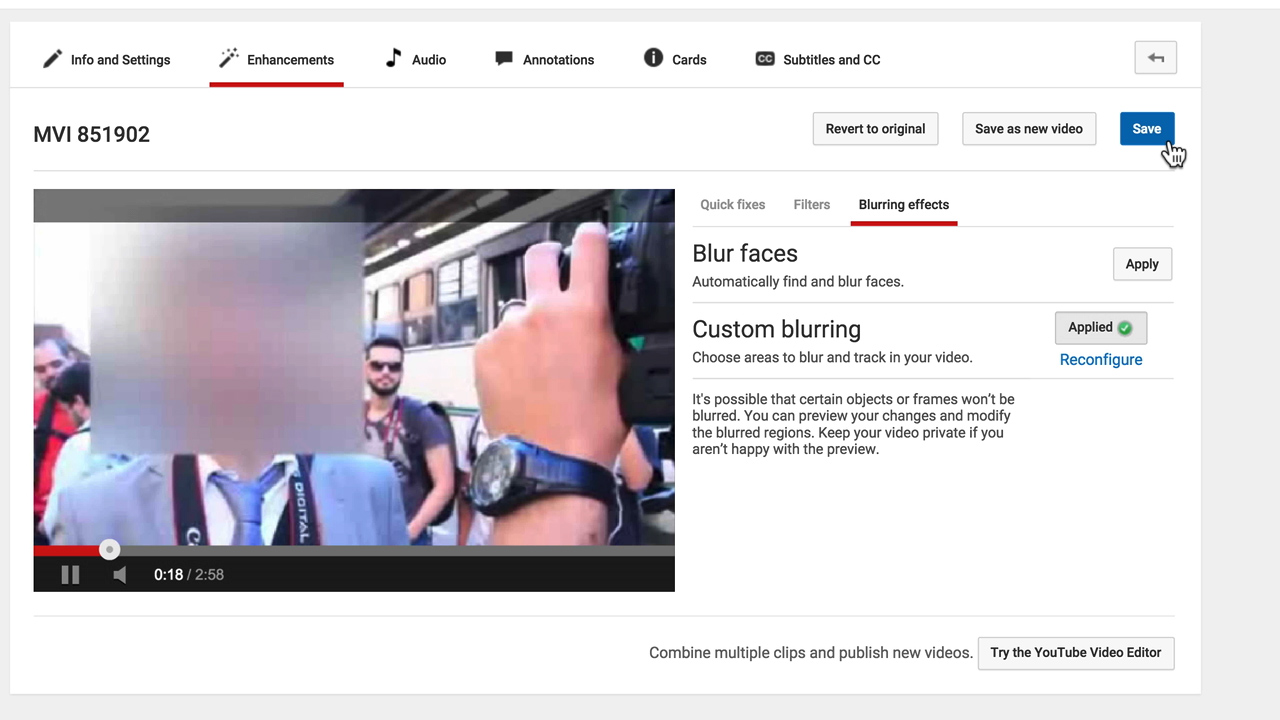

Why YouTube’s Blurring Tool Matters and Why Other Platforms Should Have One Too

We applaud YouTube for continuing to lead the way in developing and making accessible these functionalities to support citizen journalism and citizen witnessing.

In an era of exploding use of visual media by activists and citizens alike, it’s past time for other video and photo sharing platforms – from Facebook to Twitter to Snapchat, and others – to follow YouTube’s lead. In this post (which draws on an earlier blog post from 2012 when YouTube released the first version of its tool) I’ll discuss the human rights perspective on why tools like this are critical for commercial platforms to adopt.

So why does the option to pixelate faces matter?

There are two dimensions to the need for visual anonymity. One is among human rights witnesses on the ground who are trying to share testimony and experience of gross violations but protect the individuals in their videos at the same time. The other broader level is the reality that visual media is becoming the dominant form of communication, and combined with the growing prevalence of facial recognition, many more of us will need to think about contexts where we may want to exercise a selective right to visual anonymity.

The Human Rights Use Scenarios – Syria, Zimbabwe, Mexico, United States

In places like Syria, activists on the ground note how often people are identified and tracked down because of the video that they share online. Here’s Rafeeq from Homs, whose story was shared via Al-Jazeera during the early stages of the Syrian Revolution. I’ll quote him at length:

But for activists, the camera is a double-edged sword.

And here is how.

Many of my friends were arrested for protesting. However they weren’t arrested from the protest sites, but rather from the checkpoints spread across the city.

But how did Assad forces know they protested?

Government forces have special teams dedicated to monitoring protests that we film and upload to the internet.

One of my friends who was detained for a short period told me that, as he was undergoing torture in detention, he was asked by the investigator if he ever participated in rallies against the regime. When my friend denied protesting, the investigator showed him footage where his face clearly appeared in a protest.

This is when we started learning how to film rallies from angles that would clearly show the crackdown by Assad forces on protests but not the faces of those protesting.

A lot of Homs residents have become scared of the camera. This is not because there is any kind of animosity between the activists and the residents. But because of the fear the regime planted in their heart.

They know that a photo of them on the internet could result in several months of imprisonment and torture. This fear has grown as the number of arrests rose.

Residents living in opposition-controlled neighbourhoods are especially under threat of being arrested for appearing on “inciting TV networks”.

One resident who crossed to a government controlled neighbourhood was arrested at checkpoints for appearing in a footage filmed by an activist. In the footage, the man was simply removing the rubble from the street.

As a novice journalist, I have started to become very cautious about having the faces of people appear in my footage. I do not want anyone to be hurt because of me.

Similar experiences have been seen in Iran and before that in Burma.

We also see a consistent need from less documented, less public struggles to protect individuals who speak out. In fact, you may be at even greater risk if you’re the lone person speaking out in your community about, for example, as a survivor of gender-based violence in Zimbabwe or a member of an unpopular minority, like a sex worker speaking out against police violence in Macedonia, or a survivor talking about elder abuse in Pittsburgh or San Francisco. In places like Mexico where bloggers and other speaking out are frequently targeted and killed, anonymity is crucial for whistleblowers and activists denouncing both government corruption and abuse of power as well as criminal activities.

In other cases it is about hiding the identity of victims when recirculating a video showing, or even made by perpetrators (a topic WITNESS has explored thoroughly in its recent Ethical Guidelines on Eyewitness Videos) – for example videos depicting attacks on LGBT youth in Russia. In some situations it may involve blurring both victims and perpetrators in publicly shared footage so as not to jeopardize future trials or create prejudice – as Amnesty International has done with citizen and perpetrator-shot footage of military abuses in Nigeria.

The Human Rights at Stake: Why Options for Anonymity Matter for Freedom of Expression and Privacy

A consistent priority of WITNESS’ Technology Advocacy program is to give people control over their images. As part of that:

WITNESS advocates for visual anonymity functionalities like facial blurring alongside guidance on consent and privacy, and we join with allies to call for policies that respect user privacy and free expression online.

Anonymous and pseudonymous speech has a long history as a method to avoid personalization of a controversial debate, express unpopular viewpoints and reveal hidden truths or cover-ups. Think of the authors of the Federalist Papers, including many of the founding fathers of the United States, who wrote under the Publius pseudonym, or the leak of the ‘Collateral Murder’ video to Wikileaks to reveal a cover-up of the deaths of journalists in Iraq.

In an earlier post on this blog we talked about the human rights at stake when we discuss anonymity.

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers. – Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), Article 19

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence. – UDHR, Article 12

Anonymity is very much a part of the right to free speech. International human rights law addresses the right to free expression and exchange of information, as well as freedom of association in Article 19 of the UDHR (see above), and also in Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which adds that restrictions on this right “shall only be such as provided by law and are necessary: (a) For respect of the rights or reputations of others; (b) For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or public health and morals.” Further international declarations on the rights of human rights defenders also emphasize the capacity to disseminate and receive information on human rights topics.

Complementary to rights of freedom of expression is the right to freedom from arbitrary and unlawful interference with one’s privacy and correspondence, recognized both in Article 12 of the UDHR and in Article 17 of the ICCPR. The right to privacy is usually understood to include both the individual’s right to a zone of autonomy within a “private sphere” such as the home, as well as in respect to personal choices within the public sphere. In our current digital age, of course, much discussion around online Internet privacy focuses on the security of encryption, personal data and personal identity. This is why WITNESS has also joined a coalition of organizations opposed to recent moves by governments to compromise the security of encrypted communication.

Critical to an active right to both free expression and to privacy is the right to communicate anonymously and privately. Of course, this is not an absolute right – after all, anonymity can also be used, for example to cover criminal or terrorist activity. However, the active presence of options to have anonymity and no generalized restrictions on anonymity enables freedom of expression and supports the right to privacy.

Both the most recent UN Special Rapporteurs on Freedom of Opinion and Expression have affirmed the importance of this, particularly in the light of attempts to restrict various forms of anonymity.

“Restrictions of anonymity in communication… have an evident chilling effect on victims of all forms of violence and abuse, who may be reluctant to report for fear of double victimization…..They can also result in individuals’ de facto exclusion from vital social spheres, undermining their rights to expression and information, and exacerbating social inequalities.” – Frank LaRue, former United Nations Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Opinion and Expression.

“Encryption and anonymity, and the security concepts behind them, provide the privacy and security necessary for the exercise of the right to freedom of opinion and expression in the digital age,” – David Kaye, current United Nations Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Opinion and Expression

People have (in the context of real name identity debates on social networking sites) highlighted the range of people who might choose for various reasons to hide their identities – from the most obvious, for example, victims of domestic violence to members of marginalized groups like LGBT people or disabled people. “Geek Feminism” maintains a detailed and instructive wiki on the range of people affected by an insistence on real names and identity over anonymity or pseudonymity.

This recognition of the value of anonymity is also reflected in Supreme Court rulings in the US, for example, in a 1995 Supreme Court ruling in McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Commission cited by the Electronic Frontier Foundation:

“Protections for anonymous speech are vital to democratic discourse. Allowing dissenters to shield their identities frees them to express critical minority views . . . Anonymity is a shield from the tyranny of the majority. . . . It thus exemplifies the purpose behind the Bill of Rights and of the First Amendment in particular: to protect unpopular individuals from retaliation . . . at the hand of an intolerant society.”

How can we enhance anonymity by thinking about what is both in front of the lens (for example, how do we hide someone’s voice or distort someone’s voice in easy and accessible ways), but also what sits embedded in the image (for example, metadata about a filmer’s camera or phone or geolocation that could be used to identify them). Our ObscuraCam project with the Guardian Project models an approach to this at the point-of-creation, just as the new YouTube tool looks at it at point of upload and distribution.

The Consequences of Facial Recognition: Binding Identities Together

As more and more people use video to speak out because its the medium of our age, the need to give people the option to choose tools to obscure becomes even more acute. As video becomes the de facto mode of communication in a mobile-camera enabled world how do we make sure that options for anonymity are not left behind?

Such a focus on visual anonymity is bound in with other privacy debates that are relevant both to human rights activists and to a broader public. One particular debate is around the growing role of facial recognition, including within public social media networks. My former colleague Sameer Padania has talked about the ethics and practicalities of this in earlier posts here. Such concerns have been given even more impetus by experimentation with facial recognition using social network-based photos as well as by the recent failure of discussions in the US on voluntary code of conduct on use of facial recognition (in which WITNESS participated) that ended with civil society privacy advocates withdrawing in protest for the talks at the failure to agree on even basic safeguards.

The implication of this is that in an era of increasing facial recognition, the one time when you choose to say something politically unpopular, whistle-blow or otherwise speak out, can be correlated to the other 99% of your online identity, even if you try and do it outside the bounds of identity tracking. Video and photo-sharing networks like Facebook, Twitter and Snapchat can help protect identities both by offering better visual anonymity tools, but also by engaging with civil liberties and human rights advocates on the dangers of facial recognition for free speech and marginalized groups. When as live video becomes more and more common and consumerized we need to come up with visual anonymity solutions for the bystander caught live on camera and compromised for life.

Linking to an Understanding of Informed Consent

We also believe that an emphasis on tools options for visual anonymity must go hand-in-hand with a focus in user education — led by video, photo and live video sharing platforms and the social networks that are fueled by these images — in establishing an understanding of informed consent. Often in our own work we find that courageous people choose to speak out in public (and with their faces and information fully visible) despite the risks (see Erika Smith’s powerful reflection on this in the context of activists speaking out about women’s rights). They want to be found (and WITNESS supports them with tools like CameraV and broadly available ‘proof modes’). But they should fully appreciate opportunity AND risk.

Other Video and Photo-Sharing Platforms and Social Networks Need To Also Provide Options

We applaud YouTube for continuing to innovate around visual anonymity on their platform, and ask other video and photo-sharing platforms and social networks to follow their lead, as well as for independent and open-source developers to continue to push forward this area of innovation in areas such as live video. Activists and ordinary citizens need easily controlled options for this at every stage of creating and sharing media as we enter an age of digital media and communication dominated by the visual.

Want to read more? Check out Sam’s recent Op-ed on the importance of visual anonymity on WIRED.